Against the synchronous society

Table of Contents

Introduction

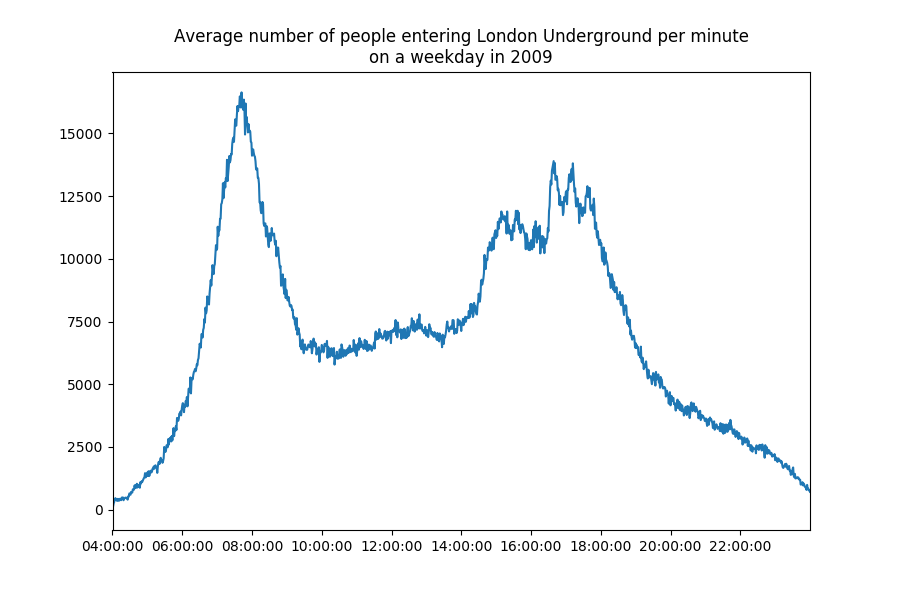

Imagine if we could turn this:

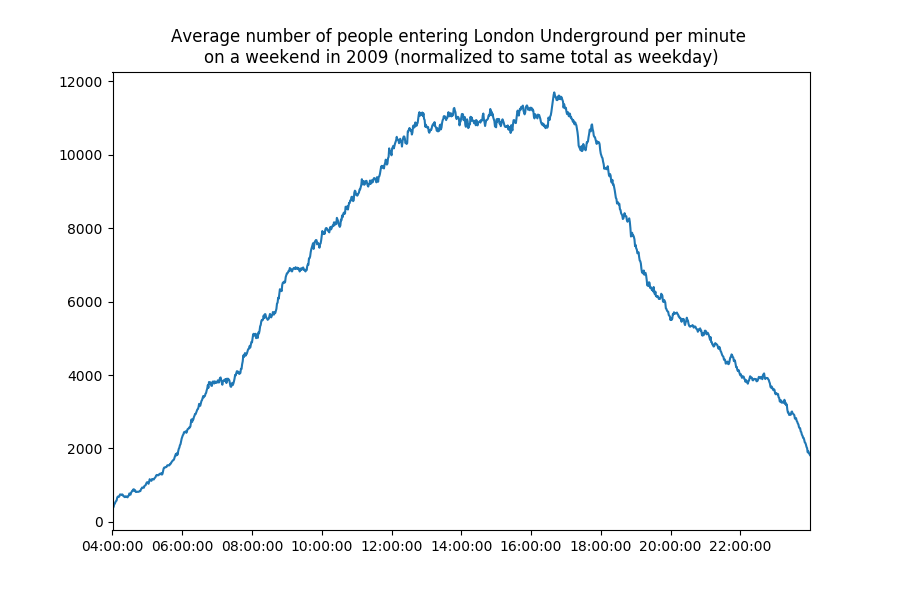

into this:

The first picture is a graph of how many people enter the London Underground network every minute on a weekday. The second graph is for the weekend, except slightly altered: I normalized it so that both graphs integrate to the same value. In other words, the same amount of people go through the network in the second graph as in the first graph.

Would you rather interact with the former or the latter usage pattern?

The data geek in me is fascinated at the fact that there are clear peaks in utilization at about 8:15 (this is the graph of entrances, remember) and, in the evening, at 17:10, 17:40 and 18:10. I'll probably play with this data further, since the dataset I used (an anonymized 5% sample of journeys taken on the TfL network one week in 2009) has some more cool things in it.

The Holden Caulfield in me is infuriated at the fact that these peaks exist.

Millions of toilets suddenly got flushed and were suddenly silenced

It's alarming how often society seems to hinge on people being in the same place at the same time, doing the same things. The drawbacks of this are immense: infrastructure has to be overprovisioned for any bursty load pattern and being inside of a bursty load pattern results in higher waiting times and isn't a pleasant experience for everyone involved. Hence it's important to investigate why this happens and whether this is always required.

Have you heard of TV pickups? Whenever a popular TV programme goes on a commercial break or ends, millions of people across the UK do the same things at the same time: they turn kettles on, open refrigerator doors, flush their toilets and so on. This causes a noticeable surge in utilization of, say, electric grids and the sewage system. As a result, service providers have to provision for it by trying to predict demand. This isn't just an academic exercise: in the case of electric energy, generators can't be brought online instantly and energy can't be stored cheaply.

In the case of the Underground network, there are times on some lines where trains arrive more frequently than every two minutes (pretty much as often as they can, given that the trains have to maintain a safe distance between each other and spend some time on the platform) and yet they still are packed between 8am and 9am. Any incident, however small, like someone holding up the doors, can result in a knock-on effect, delaying the whole line massively.

Why are people doing this to themselves?

Friday is a social construct

The weekend was a great invention (although Henry Ford's reason for giving his employees more time off was that they'd have nothing to do and hence start buying his own, and other businesses', goods). But does the weekend really have to happen at the same time for all people?

Some of the phenomena governing people's schedules are natural. It does get dark at night and people do need light. It gets cold in the winter and people need heating. But the Earth does not care whether it's the weekday or the weekend, a Wednesday or a Saturday. And yet somehow the society has decreed that Wednesday is a serious business day and any adult roaming the streets during daytime on that day might get weird stares.

Expanding on this, do working hours have to happen at the same time either? People naturally need rest, but what they don't naturally need is to be told when exactly they can work and rest. And in some types of work, like knowledge work, being told when to work is not necessary and even can be harmful.

In professional services, in most cases, the client doesn't care when the service is being performed. The client wants a tax return to be prepared: they don't want the tax return to only be prepared between 9 and 5. The client wants their investments to be managed: the investments don't need to only be managed between 9 and 5. And so on. Fixed work hours make no sense since it's not time the client is buying, it's the result. Knowledge work isn't predicated on people having to do it at the same time or even at a given time.

The fact that everybody has to work fixed hours hails from the Industrial age assembly line thinking (in fact, the term "line manager" is still used in the UK to refer to one's boss). If one part of the assembly line is missing, the assembly line doesn't work. Hence the management has to make sure that all parts of the assembly line have finished their sandwiches and are in place for when their shift starts. The whole shift also has to get their days off synchronously, as it can't function at all after a critical mass of people has taken the day off.

This is in no way an argument for longer working hours. If a person has exhausted their working capacity for the day, what's the point of holding them in the office until a given hour unless they're in a role that requires that? Some people work better when they have a set goal and some time to achieve it, to be used at their discretion. Some people work in bursts, where the output of one day can overshadow the rest of the week. Mandating fixed hours for knowledge workers means they aren't as efficient as they can be for their employer and further suffer from the utilization peaks that they themselves cause.

Corporate accounts payable, Nina speaking

Do we still need offices? Some criticize working from home as a way for employees to slack off. But if you think your people won't work unless they're watched, maybe you're hiring the wrong people. A loss of productivity from not having someone standing over their shoulder is offset by the gain in productivity from not having someone standing over their shoulder and not working in a distracting open office environment.

A benefit of offices is that they encourage communication and sharing of ideas. It's much easier to walk up to someone and ask them something, and information travels around quicker and more naturally.

On the other hand, imagine if you were a medieval scholar. They would usually work alone, with all communication with their peers done over long-form letters. Communication used to be asynchronous and there was no way the letter would be delivered as soon as it was fired off, hence there was no expectation of getting a reply in the same hour or even within the same day.

Nowadays, people are expected to respond to messages instantly, which means they have less and less uninterrupted time in which they can't be distracted.

Would you rather have a 1-hour chunk of time to do work in or 6 chunks of 10 minutes, interrupted by random phone calls, instant messenger pings and people walking up to you? The former option is much, much better if you want to do any deep work. Productivity is highly non-linear and 10 minutes of work result in better outcomes when they come after some time to ramp up. Even the anticipation that you can be interrupted can distract you and prevent you from getting into a state of flow.

Perhaps there's no need for people in the workplace to expect others to be able to instantly respond to them. In fact, slower, asynchronous communication can lead to more robust institutional memory inside of an organisation. Instead of the easy fix of tapping a colleague on the shoulder to get an answer, the worker might instead devise a solution for an issue themselves or figure it out while typing up an email, adding to the documentation and making sure fewer people have that question in the future.

Do all meetings have to happen at the same place or at the same time? Some of them do: sometimes there's no replacement for getting all stakeholders in the same room in order to come to a decision. But meetings are also a great way to waste company money, setting thousands of dollars on fire by the simple act of blocking out one hour of several people's time.

What is now a synchronous meeting (together with the flow breakage than that brings: I found that I'm more productive in a given hour if I know I don't have to go anywhere in the next hour even though the time I'm spending is the same) could be an asynchronous e-mail chain or a set of comments on the intranet that people can get to at their discretion.

Peter, you've added nothing

There's something mesmerising about being able to watch live coverage of an event. Instant notifications of a new development are a way to gratify yourself, feel like you've done something, get a small dopamine rush from getting another nugget of information. But in reality, not much has changed and this development will likely be insignificant in the end.

In this age, people have no time to think about their reaction: everything is knee-jerk, synchronous and instantaneous. An incident happens. Minutes later, we find out there is a suspect. Minutes later, there's a witch hunt across social media for the suspect and their family. Days later, the suspect is acquitted and there's another suspect. Information, not necessarily valuable or true, nowadays travels so fast that things can easily get out of control and anyone with Internet access can join in the madness.

There are a few billion times more people than you and your brain can't process inputs from them all in real time. Hence people have to operate with abstractions. Instead of constantly receiving a stream of data that interrupts your life and ultimately doesn't add anything to it, why not go to a different abstraction level and lower the sampling rate, instead reading a weekly newsletter?

If you had an investment portfolio, would you act based on looking at its performance every hour or every day? Or would you instead be aware that all the noise from the daily developments will probably cancel itself out and turn into a clearer picture of what's happened?

Bernoulli's principle works in January, too

A friend of mine works in a role where she needs to interact with offices in other countries that don't maintain UK bank holidays. What her employer does is increase her holiday allowance instead, making bank holidays a normal working day. I think this is amazing. The time when most people are away on holiday is the best time to get some work done in the office and the time when most people are in the office is the best time to go shopping, visit doctors, go to a museum and do all other sorts of other life admin things.

From a cultural point of view, public holidays are amazing. From a logistical point of view, they're a nightmare. If everybody is having a holiday, nobody is, and the fact that everyone is observing the holiday at the same time yet again creates usage peaks in all sorts of places.

For example, synchronous buying of presents means that retailers have to overstock their wares in run-up to major holidays, say, Christmas, and, worse even, have to offload all the Baylis and Harding soap sets at fire sale prices starting at about dinnertime on the 24th December. Hilariously, the best time to shop for Christmas presents is in January.

And most holidays are taken around these times too. People in the UK get fined and can even get prosecuted for taking their children on holiday during term time. The fine is usually less than the difference in price for airline tickets and accommodation between taking a holiday during term time and outside of term time, but that price difference is just a consequence of the difference in demand between those times. There are still planes in January, but they're... emptier. And airports aren't such an unpleasant experience.

In any case, most parents are now coerced to take holidays only outside term time, which has a knock-on effect on flight/accommodation usage and prices.

Conclusion

I honestly don't know how to solve most of these problems. Maybe with the rise of remote work and teleconferencing this will naturally go away, moving us to a future where nobody can have a case of the Mondays any more. Some companies are embracing parts of being asynchronous already, like Basecamp (ex-37 Signals) who list the benefits of remote work and fewer meetings in REWORK.

It's more difficult on the social side. I dream of a relationship where we agree to celebrate all holidays (Christmas, Easter, Valentine's etc.) a few days later to take advantage of the trough in the demand that comes after the peak. In addition, to be efficient, education indeed has to be synchronous: one teacher educates multiple children and any of them skipping material will result in them having to catch up, delaying the whole year. I had a chat about this with a friend once: what if education were much more granular, with children (or their parents) being able to pick and choose when their child takes a given class? Staggered school shifts, perhaps?